Dear Korean,

For a culture so aware of their international image, and so eager to take the international stage, ("Hey, look everybody! A Korean has a lead role on a major network TV series!" "Do you know the Korean Wave?") why do Koreans seem hypersensitive to criticism from non-Koreans? I have heard defensive Koreans make outlandish claims about their culture and people that are completely unrealistic and patently untrue, even while discussing topics Koreans themselves recognize they need to improve, simply because a non-Korean is pointing out the flaws: what is going on there?

Under what conditions, if any, would Koreans be ready and open to accepting constructive criticism from non-Koreans, about Korea's society/culture/business climate/etc.? Who DOES have the right to criticize Korea? And what about non-Koreans who have moved to Korea, studied it, and lived there for a long time, and the 1.5 people in other countries? What should I say to Koreans who get defensive, or am I just butting my head against a wall by bringing up such topics with Koreans, and would do better to surrender, and praise the virtues of kimchi, and leave the controversies be?

Roboseyo

Dear Roboseyo,

The hypersensitivity that you speak of is absolutely true, but you did not need the Korean to tell you that. Everything you said about Koreans taking criticisms poorly from a non-Korean is all true: they get extremely animated as if they were personally insulted, they get defensive, and often make counter-claims that are either unpersuasive or borderline absurd.

In fact, for many expats the complaint is not about Koreans’ hypersensitivity; it is their absurd arguments in responding to criticisms. Where do the absurd arguments about Korean superiority come from? As it turns out, the hypersensitivity and the absurdity questions are related, so read on.

Korean People's Hypersensitivity

First, let us eliminate one popular hypothesis from the running. Some observers posit that Korean culture is simply not a “criticizing culture”, because it emphasizes homogeneity

and harmony. Because Koreans are reluctant to criticize one another, the theory goes, any amount of criticism is considered a very bold act, and often deeply insulting.

and harmony. Because Koreans are reluctant to criticize one another, the theory goes, any amount of criticism is considered a very bold act, and often deeply insulting.The Korean can unequivocally say that this theory is 100 percent crap, because Koreans liberally criticize their country and each other. And truly, the severe and ignorant nature of their criticisms aimed toward their fellow Koreans makes criticisms from expats look like sprinkles of flowers and baby powder.

Just to give a couple of examples, the Korean took less than 10 minutes of Korean news search to find these choice comments. Please note that the Korean did not say anything about the comments’ coherence or persuasiveness. The Korean will not be responsible for the headache following the reading of these comments:

About Anti-U.S. Beef Protests, titled “Violent suppression against illegal protest is a matter of course”:

“Amnesty International recognized the illegality of Candlelight Protests as well. From the perspective of the riot police, they have to fight the zombie dog packs in a one-to-one hundred numerical disadvantage. It’s enough to make one scared for his life. It’s natural to strain a little in order to protect your own body from extreme fear and anxiety. It’s the same as the fact that in any war there is a mass killing. It’s the same as the situation in which a burglar broke into the house, and in order to protect your property, you could fight the running burglar and end up beat him like a dog in a bit of excitement. The problem is with the punks who tried to overturn the country and turned the streets into lawless hellhole with something that doesn’t even make sense. Keep in mind that human rights organizations always represent the weaker side’s position. Don’t human rights organizations always side with the lone murder?”

About South Korean woman being shot in North Korea, titled “All of you move to North Korea”:

“Freakin’ commies, way to ruin my morning. Stop criticizing the president and cross over if you like North Korea so much. Except you, regular people have to go on living and they have a lot to do for that. Why do you say nothing to the infamous villain Kim Jong-Il and raise hell with our president? If you were born in North Korea you don’t even get the right to run your mouth. That woman will follow you and curse you all your life in the netherworld. Why do these punks without common sense keep on running their mouth? Thanks to the Roh Moo-Hyeon administration that let go of the Internet even trashy citizens are all protected.”

(Note to expat complainers: Still think all Koreans blindly follow the beef protesters while being silent on the North Korean shooting? See what you’re missing when you don’t read Korean media directly?)

Okay then: if search for harmony is not the answer, what makes Koreans hypersensitive to criticisms from non-Koreans? The hints to the answer can be found in Roboseyo’s question. Koreans care very much about their international image, but at the same time they are deeply insecure about the same image. Such attitudes are two sides of the same coin, and the coin is called “Nationalistic Zeal”.

Remember what the Korean wrote in the previous post in this series: the keystone knowledge for understanding modern Korea is the fact that Korea went from abject poverty to one of the world’s economic leaders. Understanding Korean people’s hypersensitivity in this respect is not an exception.

How did the amazing economic growth lead to such hypersensitivity? One obvious way is that Koreans are justifiably proud of their achievement. Again, understanding the astounding magnitude of this growth is the key. In 1962, per capita GDP of Korea was $87. 45 years later in 2007, per capita GDP of Korea was $24,783.

Let’s dice those numbers around. To grow from $87 to $24,783 in 45 years, there has to be a return of 13.4 percent every year for 45 years. Not even the greatest hedge fund manager in the history of Wall Street can do that. To grow from $87 to $24,783 in 45 years, the productivity per person has to double every 5~6 years. In other words, every single person in Korea had to double his/her productivity every 5~6 years for 8~9 times in a row.

This is truly a towering achievement. This has never happened in human history before Koreans did. And Koreans are legitimately proud of their country and themselves for having achieved it. (Of course, the Chinese are now doing what Koreans did. And it should come as no surprise that the same crazed nationalism grips China as well.)

But this nationalistic zeal is not just an outcome of the spectacular growth; it has been a very important tool of the growth as well. After all, this level of development does not come without an enormous amount of sacrifice from all sectors of the society. Thus, Korean employees were asked to work 18 hours a day; Korean employees’ wives were asked to put up with the binge drinking that their husbands would engage in to relieve the stress; Korean students were asked to prove their worth through ridiculously competitive exams; and so on.

Enduring through all this stuff requires a strong motivatioon to look past the shittiness of the current situation and look to the future. Of course the desperate desire to escape poverty was a strong motivator for everyone involved in this process. But there is always more to be done. As Napoleon said, “A man does not have himself killed for a half-pence a day or for a petty distinction; you must speak to the soul in order to electrify him.”

Enduring through all this stuff requires a strong motivatioon to look past the shittiness of the current situation and look to the future. Of course the desperate desire to escape poverty was a strong motivator for everyone involved in this process. But there is always more to be done. As Napoleon said, “A man does not have himself killed for a half-pence a day or for a petty distinction; you must speak to the soul in order to electrify him.”What speaks to the Korean soul? The tried-and-true method that works on every soul. First, glorify the nation’s past history by any means possible. Second, pump the citizens up with national pride over the glorified past history. Third, blame external factors (= other countries) for the current economic plight. Fourth, remind the citizens again about the glory days of the past, and exhort them to reconstructing those moments. Presto! Suddenly you have a nation full of explosively motivated people.

[Warning! Godwin’s Law moment ahead!] Guess who mastered this formula for the first time? None other than Adolf Hitler. Let’s be clear: the Korean does not intend to say anything positive about Hitler. But the method through which the Mustachioed Symbol of Evil motivated Germans enough to turn the post-WWI scrap heap that was Germany into World War-capable economy at least deserves some attention. And the same method, give or take minor variations on the theme, was successfully used in more or less all countries that achieved impressive economic growth in the 20th century. Such countries include Germany, Russia, Italy, Japan, and yes, Korea. (And China.)

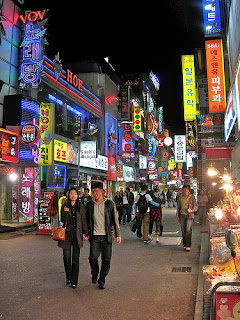

Korea’s process fits this pattern perfectly. First, Korea’s glorious past. A nation of power,

evidenced by the huge territory that once stretched all the way into Manchuria 15 centuries ago! A nation of science, evidenced by the first armored ship in the world! The first metal printing press in the world! The most scientific alphabet in the world! A nation of artistic genius, with stunningly beautiful Buddhist temples and light turquois ceramics whose colors still cannot be replicated to this day! How can you not get pumped up with all this glory? All this stuff is constantly fed to the people through school textbooks, state-controlled media outlets, and totally objective reports from various university professors.

evidenced by the huge territory that once stretched all the way into Manchuria 15 centuries ago! A nation of science, evidenced by the first armored ship in the world! The first metal printing press in the world! The most scientific alphabet in the world! A nation of artistic genius, with stunningly beautiful Buddhist temples and light turquois ceramics whose colors still cannot be replicated to this day! How can you not get pumped up with all this glory? All this stuff is constantly fed to the people through school textbooks, state-controlled media outlets, and totally objective reports from various university professors.Then onto blaming other countries – which one will it be? How about Japan? All it did was to occupy Korea for 36 years, tortured and killed people, forced numerous Korean women into an institutionalized prostitution, and perform human experimentation. But we can’t forget North Korea either. Those commies almost ruined everything, and are still plotting to ruin everything. It's clear that Korea should be in a better place than where we are now given our glorious history, but it has to be those jjokbari (nips) and bbalgaeng'i (commies) that are holding us back. Well, no more! Onto economic development!

(Does this sound overly simplistic? But you just have to take the Korean's word for it that this is exactly how it happens. This message was constantly hammered in to the young Korean and his classmates throughout the Korean's school life.)

And this is the point from which both absurdity and hypersensitivity questions can be answered. Let's address the absurdity question first.

While drumming up national pride through history sounds manipulative, the Korean version of this process is, in a larger context, relatively tame. The historical account of Korea told in Korea is, by and large, true. At least Korea did not – officially – make up ancient history like Japan did, or elevate racism to the level of pseudo-science like Nazi Germany did. It is more on par with Italy’s attitude towards the Roman empire, which like Korea attempted to link back to its own history that is, while genuine, too old to be truly relevant in the modern era.

But there is no denying that, although they may be true, Korean historical accounts told by Koreans are consistently and strongly slanted towards achieving the objective stated earlier. This slant is then reinforced over and over within private channels of information (= people without deep knowledge of history simply talking to one another,) because hey, who doesn't like hearing good things about their past? As information reverberates within this self-contained echo chamber, it is often distorted to an absurd proportion.

But there is no denying that, although they may be true, Korean historical accounts told by Koreans are consistently and strongly slanted towards achieving the objective stated earlier. This slant is then reinforced over and over within private channels of information (= people without deep knowledge of history simply talking to one another,) because hey, who doesn't like hearing good things about their past? As information reverberates within this self-contained echo chamber, it is often distorted to an absurd proportion.This problem is compounded by the fact that, like any country in the world, not everyone in Korea is fully knowledgeable about her own nation’s history. Despite what an unsuspecting expat may think, Koreans do not sit and ponder for days upon days fine-tuning the arguments for Korean superiority. All they have are a few nuggets of information about Korea that they have collected through school and media. And it is precisely the schools and the media that relentlessly push out such slanted information.

But many Koreans do not have the proper perspective to evaluate this information they receive, because they have never spent much time examining other cultures. Even if they did have a proper perspective, they do not have the English skills to properly communicate the subtle nuances.

(Aside: in comparison, expats in Korea tend to be well-educated and well-traveled, likely having a better vantage point to evaluate Korean culture and society within a greater context. More importantly, where a certain culture stands within the world is something that is constantly on an expat’s mind. After all, expats are in a foreign country to do (among other things) exactly that!)

So when the irresistible compulsion to defend Korea against non-Korean-generated criticism of Korea strikes an average Korean, she is often poorly equipped to do so. Her argumentative tools simply are not adequate to properly express her fervor. Therefore, she flails about as she tries to stand her ground, and frequently resorts to poor rhetoric and obstinate denial.

For example, one of the typical responses from Koreans that Roboseyo cites is: “Go easy on us, we are just a developing nation!” To which Roboseyo answers thusly:

"Answer: Put very simply:

Still developing:

Finished developing:

Congratulations! You're part of the club! You're playing with the big kids now!

Congratulations! You're part of the club! You're playing with the big kids now!In terms of infrastructure and wealth, Korea is no longer a developing nation. Top fifteen economy in the world, people from South Asia coming HERE to work and send money home -- in the ways of the won, Korea's made it. It's a major player. Other countries look to Korea's development model to figure out how to raise their standard of living and set up infrastructure. One of the drags that comes with being one of the big boys is being a big target, and people pay more attention, and take more shots at big targets. Griping about facing criticism from the international community that Korea worked so hard to join, is like the little boy who wants to play soccer with his older brother's big friends, and then cries when they knock him down with a sliding tackle."

But with more knowledge and ability for nuanced expression, the proverbial Korean could have said this to Roboseyo instead:

“While Korea has an appearance of a fully developed nation, the appearance is more of a façade because such development was only actualized in the last two decades at best. The leadership in the society, primarily consisted of people in their 50s and above, grew up in a pre-modern era. Their paradigms are often stuck in the pre-modern era, and they perpetuate such paradigms into the younger generation through the educational process.

To explain this within your simile, sure it is annoying that the little boy cries after one sliding tackle. But for a little boy, a sliding tackle from a big boy really hurts! His desire to play with the big boys does not change the fact that his body is not ready to take the big boys’ game.”

One may disagree with this explanation, but at least this explanation is no longer absurd. But giving this type of explanation requires a certain level of knowledge, acquired by investing the time to think about this issue, as well as a certain level of eloquence in English. Many Koreans have neither.

Now, the hypersensitivity part. Note that the unit of measurement of the nationalistic zeal is a nation. The glorified history was shared as a nation. It was other nations that imposed difficulties to our own nation, and we as a nation suffered the consequences. And now, we as a nation are gearing up for ascendence, and other nations are doing the same.

It is crucial to understand that in the worldview of a nationalist, each and every person in the world operates as a member of a team called "United States of America", "Brazil", "Thailand", "South Africa", "France", etc. And each team are striving to outdo one another in a giant world race for power, be it economic, political, social, cultural or any other type one can think of.

why World Cup soccer is so popular around the world? It's not just that soccer is joga bonito. World Cup is so popular because nothing actualizes the world-race in the minds of nationalists quite like a bunch of countries playing a ballgame.)

why World Cup soccer is so popular around the world? It's not just that soccer is joga bonito. World Cup is so popular because nothing actualizes the world-race in the minds of nationalists quite like a bunch of countries playing a ballgame.)And here is the reason why Koreans get hypersensitive to criticisms from non-Koreans. Koreans, as faithful nationalists, are deeply concerned about their own team. So deep down, Koreans love hearing what non-Koreans have to say about them. After all, Koreans know that Korea has much to learn to become a leader in the world, and they are keen on listening to any pointers.

But Koreans nonetheless often respond negatively to a non-Korean generated criticism, for two reasons. First is the reflexive emotional response. Beacuse a member of another team just criticized your team, something that you hold dear, you will react automatically. (Ever tried criticizing Ohio State football in Ohio? It's that type of reaction, on Barry Bonds-grade steroids.) It is something along the lines of: "Don't tell me how to run our own team! You think we don't know our problems? Go mind your own fucking business!"

Second reason is that Koreans genuinely worry that criticism from a non-Korean would actively damage the standing of Korea within the world. (And the theme of nationalism as an outcome as well as the tool for that outcome shows once again.) When your team appears weak, other teams will take advantage of it. So you must repel such criticism from a non-Korean, regardless of the validity of that criticism. And the defensiveness for Korea comes out in full swing.

As a Non-Korean, What Can I Do to Become a Constructive Critic?

Let’s move onto the second part of Roboseyo’s question – what can you do, as a non-Korean, to become a constructive critic of Korea?

The most important thing is to understand the level of difficulty involved in being a critic who is listened to, not who is rejected outright. Non-Koreans and expats think they can competently criticize Korean society like they would criticize the current Medicare system. This error is understandable, because virtually anyone thinks s/he can write and criticize without receiving much specialized learning at all.

But make no mistake – there are easy and hard criticisms to make, and the gap

in difficulty between the two are as wide as the Pacific Ocean. For example, after about an hour of lesson at the driving range, virtually anyone can swing a golf club. But if an American’s criticism of Medicare to another American is like a doing a round of golf in a neighborhood park, an American’s criticism of Korean society to Korean people is like teeing up at the Pebble Beach, if the entire Pebble Beach were covered in landmines. It takes abundant caution, surgically precise skills, and keen powers of observation. Lacking any of them would lead to the situation literally blowing up on your face.

in difficulty between the two are as wide as the Pacific Ocean. For example, after about an hour of lesson at the driving range, virtually anyone can swing a golf club. But if an American’s criticism of Medicare to another American is like a doing a round of golf in a neighborhood park, an American’s criticism of Korean society to Korean people is like teeing up at the Pebble Beach, if the entire Pebble Beach were covered in landmines. It takes abundant caution, surgically precise skills, and keen powers of observation. Lacking any of them would lead to the situation literally blowing up on your face.  Answer: Rappers! The Korean dares anyone to come up with a better analogy. What do you think all the blings, Cristals, and Bentleys are about? Because blackness has always been associated with (among other things) poverty, black rappers go on a rampage of overcompensation to ensure that no one dares think that they are poor, even at the expense of what may be considered crass, in-your-face lyrics and accessories.

Answer: Rappers! The Korean dares anyone to come up with a better analogy. What do you think all the blings, Cristals, and Bentleys are about? Because blackness has always been associated with (among other things) poverty, black rappers go on a rampage of overcompensation to ensure that no one dares think that they are poor, even at the expense of what may be considered crass, in-your-face lyrics and accessories.  for this: Korean people deep down are keen on hearing what non-Koreans have to say about them. They are receptive to what you have to say, although it often does feel like ramming your head against a brick wall. Criticize skillfully, and Korean people will listen to you. Take comfort in small milestones, and continue to move forward. Like Coach Anzai says, “When you give up, the game is over.”

for this: Korean people deep down are keen on hearing what non-Koreans have to say about them. They are receptive to what you have to say, although it often does feel like ramming your head against a brick wall. Criticize skillfully, and Korean people will listen to you. Take comfort in small milestones, and continue to move forward. Like Coach Anzai says, “When you give up, the game is over.” 2. polemical writing sticks in peoples' heads for longer than diplomatic writing, which means it ultimately has a higher chance of changing a person's pattern of thinking!

3. polemical writing stirs up emotions, which means it will start more discussions, than diplomatic writing, which might not poke through someone's guard.

Bare fact: A scalpel is a better surgical tool than a pillow, and sometimes, a social problem must be sharply criticized to bring about change; gentle phrases just won't stir up a strong enough reaction.”

Aristotle identified ethos, logos, and pathos as the three modes of persuasion. With ethos, the speaker establishes her knowledge and credibility. With logos, the speaker takes logical steps to her conclusion. With pathos, the speaker makes an emotional connection with the listener and convinces the listener to accept her conclusion. In many situations, one or two of them may suffice. But remember, this is Pebble Beach minefield. Successful criticism of Korea from a non-Korean could only come when there is an abundance of all three modes.

Aristotle identified ethos, logos, and pathos as the three modes of persuasion. With ethos, the speaker establishes her knowledge and credibility. With logos, the speaker takes logical steps to her conclusion. With pathos, the speaker makes an emotional connection with the listener and convinces the listener to accept her conclusion. In many situations, one or two of them may suffice. But remember, this is Pebble Beach minefield. Successful criticism of Korea from a non-Korean could only come when there is an abundance of all three modes. After several rounds, the Korean was struck by the fact that the most fatal strike is the one that appears the most effortless. Three different matadors fought six bulls, and it was clear that the inept matador was the one who was expending the most effort. He would stab and stab at the bull with all of his strength, but the bull continued to stand up and charge. On the other hand, the most skillful matador only needed one shot; his sword slipped through the bull’s body like it was made of butter, and the bull fell within seconds. This should be the image of the most effective criticism.

After several rounds, the Korean was struck by the fact that the most fatal strike is the one that appears the most effortless. Three different matadors fought six bulls, and it was clear that the inept matador was the one who was expending the most effort. He would stab and stab at the bull with all of his strength, but the bull continued to stand up and charge. On the other hand, the most skillful matador only needed one shot; his sword slipped through the bull’s body like it was made of butter, and the bull fell within seconds. This should be the image of the most effective criticism.

Rob has always been a friend of my blog, and so I was more than happy to write a little something about Jeollanam-do for his site. Not happy enough to get around to writing it in a timely manner, mind you, but happy nonetheless. In all fairness typing "a little something" isn't as easy for me as it is for my peers in Seoul and Busan. As you know, outside of Seoul the hallmarks of civilization are spotty at best, and it's not like I can just sit down in front of a computer---com-pu-ter?---and bang something out. And even if I could, we only have electricity four hours a week, and I like others in my little fishing village use it almost exclusively for the publication of Communist pamphlets. But during final exam time at my Confucian academy I was able to sneak out for a few weeks and travel north along Jeollanam-do's road and into Gwangju's general store to put in some time on our province's wordprocessor. The trip took longer than expected because the road was full of protestors participating in a stick rally against American beef. They haven't invented fire in Gwangju yet, so we've been immune from the insane candlelight riots that have taken hold in Korea's capital.

Rob has always been a friend of my blog, and so I was more than happy to write a little something about Jeollanam-do for his site. Not happy enough to get around to writing it in a timely manner, mind you, but happy nonetheless. In all fairness typing "a little something" isn't as easy for me as it is for my peers in Seoul and Busan. As you know, outside of Seoul the hallmarks of civilization are spotty at best, and it's not like I can just sit down in front of a computer---com-pu-ter?---and bang something out. And even if I could, we only have electricity four hours a week, and I like others in my little fishing village use it almost exclusively for the publication of Communist pamphlets. But during final exam time at my Confucian academy I was able to sneak out for a few weeks and travel north along Jeollanam-do's road and into Gwangju's general store to put in some time on our province's wordprocessor. The trip took longer than expected because the road was full of protestors participating in a stick rally against American beef. They haven't invented fire in Gwangju yet, so we've been immune from the insane candlelight riots that have taken hold in Korea's capital.

Hyangiram: I consider

Hyangiram: I consider