So on Facebook tonight, from a handful of friends, the word was that KBS only aired 20 minutes of news during the 9pm broadcast, and then finished the hour off with marine wildlife.

The Korea Times reported that KBS reporters have walked off the job as a way of demanding the resignation of the CEO, who is accused of trying to influence programming to be more friendly to the president, and to appoint people friendly to the president to important positions in the organization. More here.

The Sewol Tragedy once again plays into this series of events: the public accounting for poor media coverage of the disaster and rescue started days ago, with apologies and self-reflection. One aspect of that has been, again, suppressing or massaging stories in order to make sure the President appears in a positive light.

Related, on May 1st, Reporters Without Borders released its 2014 World Press Freedom Index, which reports on the media environment of the previous year. Visit it here. Read The Press Freedom Index's methodology here. (PDF) South Korea ranked 57th in the world, seven places down from last year.

Korea's press freedom index rankings have been on a steady decline for a while. Here are the results since 2002: The first column is the year. The second column is South Korea's ranking in the world, and the third is Korea's score. A 0.00 score means a perfectly free press, and a 100 score means a total lack of press freedom. The scoring system was re-calibrated in 2013, when Reporters Without Borders started tracking incidents of censorship, and other countable items, themselves, instead of through the word of their contacts (hence the big jump from '12 to '13).

Year Rank Score

2002 39 10.50

2003 49 9.17

2004 48 11.13

2005 34 7.5

2006 31 7.75

2007 39 12.13

2008 47 9

2009 69 15.67 (low point due to the 2008 beef protests and government response)

2010 42 13.33

'11-12 44 12.67

2013 50 24.48

2014 57 25.66

The high point for Korea's press freedom was 2006, meaning that in 2005, South Korean media faced less censorship and manipulation than any other year. Since then, with a blip in 2010 (after a low point in 2009), the slide has been fairly steady, dropping between 2 and 8 places per year. These drops were not large enough in any one year to attract special mention in any of Reporters Without Borders' global summary reports, but dropping 26 places from 2006 to 2014... bothers me.

Freedom House, which also reports on press freedom worldwide, downgraded South Korea's rating from "Free" to "Partly Free" in 2011, again due to government intervention in media coverage -- presidential appointments to important media outlet positions, again. (More on the 2014 report here) (Freedom House's 2013 report on South Korea here. Nice and concise.)

In 2011, Frank LaRue, special rapporteur to the UN, also reported on freedom of expression in South Korea. His final UN repot, however, mentions South Korea in specific only a handful of times: this Amnesty International report puts those points all in one place.

The National Security Act - read Amnesty International's report -- was written in 1948, and has a kind of a cold war "Blank Check" feel to it, with some vague wording about "anti-state activity" that can cover just about anything, in case the KCIA ever needs to trump up some charges. Read up.

Now, I get it, that as recently as the 1980s, South Korea had extremely limited press freedom, and robust and vigorous institutions don't just install themselves overnight-especially institutions with as many moving parts as a free press, and especially installed right on top of a non-free, censored and manipulated press. And being really healthy for a while doesn't mean a long-free press can't suddenly take a nosedive (even the USA, our self-proclaimed model democracy, has had some embarrassing drops). On the other hand, the fact that South Korea's not only backsliding, but steadily backsliding over an extended period, bugs me a lot, and I find it cynical and spurious that the fangless North Korean threat is still being invoked in order to block that website, delete that tweet, and hound that reporter. The antidote for speech you don't like is more speech, not censorship, and a robust democracy is confident enough in itself that it can bear the existence of a fringe movement without flipping the f-stop out.

I and a few friends have been working on a podcast lately called the Cafe Seoul Podcast, and our latest episode was inspired by Korea's slide in press freedom rankings, but the KBS walkout seems like a good time to share it.

Here is the podcast episode. In it, I interview John Power, who has worked as a reporter for a few of Korea's English language outlets. In case you aren't interested in the other stuff (awesome as it is), the interview starts at 33:40.

The darn thing won't embed, so here's the link.

The interview was edited a bit for length, so here is the raw cut of the full interview... because especially when the topic is free speech, I feel like listeners deserve to hear all the questions and answers.

And here's the link for this one.

And here it is on SoundCloud.

And here are the questions I asked John Power, and the times you can skip to, to find them:

2:00 - "Tell us about yourself"

2:30 - "Why is press freedom vital for a healthy democracy?"

3:18 - "Freedom house reports press freedom worldwide is on the decline, and other countries in Asia are dropping or ranked lowly on press freedom indexes; what's going on, and do you think the conditions in other countries affect what happens in Korea?"

6:00 - "Who are some of the players that are affecting press freedom in Korea for the better or for the worse?"

9:20 - [Bearing in mind cases like Na Gom-su-da and the blogger Minerva cases] "Can you explain for our readers what a chilling effect?"

10:30 - "In your opinion, what are steps that cold be taken to get Korea climbing instead of dropping in these press freedom indexes?"

14:50 - "In response to what some see as the corporatization of Korean (and world) media, some have pointed to social media and citizen journalism as the antidote… what are your thoughts on this?

17:35 - "Who do you trust more to handle Korea’s media responsibly: the chaebol, the government, “citizen journalists” or who?"

18:45 - Other Cafe Seoul cast members join.

20:40 - The National Security Act is still invoked because "There are North Korean spies out there" - is that a big enough threat to be concerned about, and censor, media?

|

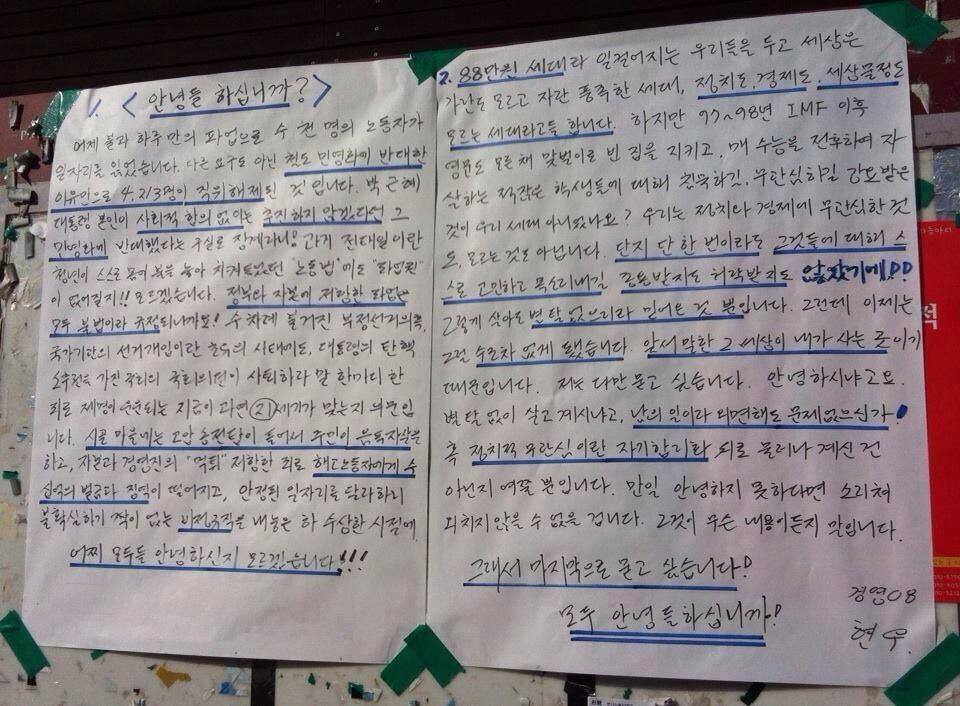

| Photo from a Facebook friend: turtles gettin' busy |

The Sewol Tragedy once again plays into this series of events: the public accounting for poor media coverage of the disaster and rescue started days ago, with apologies and self-reflection. One aspect of that has been, again, suppressing or massaging stories in order to make sure the President appears in a positive light.

Related, on May 1st, Reporters Without Borders released its 2014 World Press Freedom Index, which reports on the media environment of the previous year. Visit it here. Read The Press Freedom Index's methodology here. (PDF) South Korea ranked 57th in the world, seven places down from last year.

Korea's press freedom index rankings have been on a steady decline for a while. Here are the results since 2002: The first column is the year. The second column is South Korea's ranking in the world, and the third is Korea's score. A 0.00 score means a perfectly free press, and a 100 score means a total lack of press freedom. The scoring system was re-calibrated in 2013, when Reporters Without Borders started tracking incidents of censorship, and other countable items, themselves, instead of through the word of their contacts (hence the big jump from '12 to '13).

Year Rank Score

2002 39 10.50

2003 49 9.17

2004 48 11.13

2005 34 7.5

2006 31 7.75

2007 39 12.13

2008 47 9

2009 69 15.67 (low point due to the 2008 beef protests and government response)

2010 42 13.33

'11-12 44 12.67

2013 50 24.48

2014 57 25.66

The high point for Korea's press freedom was 2006, meaning that in 2005, South Korean media faced less censorship and manipulation than any other year. Since then, with a blip in 2010 (after a low point in 2009), the slide has been fairly steady, dropping between 2 and 8 places per year. These drops were not large enough in any one year to attract special mention in any of Reporters Without Borders' global summary reports, but dropping 26 places from 2006 to 2014... bothers me.

Freedom House, which also reports on press freedom worldwide, downgraded South Korea's rating from "Free" to "Partly Free" in 2011, again due to government intervention in media coverage -- presidential appointments to important media outlet positions, again. (More on the 2014 report here) (Freedom House's 2013 report on South Korea here. Nice and concise.)

In 2011, Frank LaRue, special rapporteur to the UN, also reported on freedom of expression in South Korea. His final UN repot, however, mentions South Korea in specific only a handful of times: this Amnesty International report puts those points all in one place.

The National Security Act - read Amnesty International's report -- was written in 1948, and has a kind of a cold war "Blank Check" feel to it, with some vague wording about "anti-state activity" that can cover just about anything, in case the KCIA ever needs to trump up some charges. Read up.

Now, I get it, that as recently as the 1980s, South Korea had extremely limited press freedom, and robust and vigorous institutions don't just install themselves overnight-especially institutions with as many moving parts as a free press, and especially installed right on top of a non-free, censored and manipulated press. And being really healthy for a while doesn't mean a long-free press can't suddenly take a nosedive (even the USA, our self-proclaimed model democracy, has had some embarrassing drops). On the other hand, the fact that South Korea's not only backsliding, but steadily backsliding over an extended period, bugs me a lot, and I find it cynical and spurious that the fangless North Korean threat is still being invoked in order to block that website, delete that tweet, and hound that reporter. The antidote for speech you don't like is more speech, not censorship, and a robust democracy is confident enough in itself that it can bear the existence of a fringe movement without flipping the f-stop out.

I and a few friends have been working on a podcast lately called the Cafe Seoul Podcast, and our latest episode was inspired by Korea's slide in press freedom rankings, but the KBS walkout seems like a good time to share it.

Here is the podcast episode. In it, I interview John Power, who has worked as a reporter for a few of Korea's English language outlets. In case you aren't interested in the other stuff (awesome as it is), the interview starts at 33:40.

The darn thing won't embed, so here's the link.

The interview was edited a bit for length, so here is the raw cut of the full interview... because especially when the topic is free speech, I feel like listeners deserve to hear all the questions and answers.

And here's the link for this one.

And here it is on SoundCloud.

And here are the questions I asked John Power, and the times you can skip to, to find them:

2:00 - "Tell us about yourself"

2:30 - "Why is press freedom vital for a healthy democracy?"

3:18 - "Freedom house reports press freedom worldwide is on the decline, and other countries in Asia are dropping or ranked lowly on press freedom indexes; what's going on, and do you think the conditions in other countries affect what happens in Korea?"

6:00 - "Who are some of the players that are affecting press freedom in Korea for the better or for the worse?"

9:20 - [Bearing in mind cases like Na Gom-su-da and the blogger Minerva cases] "Can you explain for our readers what a chilling effect?"

10:30 - "In your opinion, what are steps that cold be taken to get Korea climbing instead of dropping in these press freedom indexes?"

14:50 - "In response to what some see as the corporatization of Korean (and world) media, some have pointed to social media and citizen journalism as the antidote… what are your thoughts on this?

17:35 - "Who do you trust more to handle Korea’s media responsibly: the chaebol, the government, “citizen journalists” or who?"

18:45 - Other Cafe Seoul cast members join.

20:40 - The National Security Act is still invoked because "There are North Korean spies out there" - is that a big enough threat to be concerned about, and censor, media?

24:00 - Differences between the way Korea is reported on in English, and in Korean.

26:15 - Have you ever had a story you worked on censored? Have you ever self-censored?